Who needs sleep?

I do, and lots of it. Without sleep, I don't function well. I get grouchy, sloppy, despondent, and my activity slows to a turtle's pace. None of those descriptors are what you want attached to your doctor when your life is on the line.

Even though recent laws have been passed that restrict resident work hours to 80 hours per week, the time honored tradition of the 30 hour shift still persists. For most people, a 10 hour work day is a long one. Imagine doing that, then doing it again, and then doing it one more time, back-to-back-to-back, without a break and under conditions of extremely high intensity, when any mistake on your part could result in the death of someone else.

Except for my residency colleagues, I don't think anyone else reading this can truly understand how difficult it is. It is something that can only be appreciated through experience. And we do it every 5th night. All hyperbole aside, we are not superheroes. We adapt, we learn to pace ourselves, we learn to prioritize, we sleep when things are (rarely) quiet. Thank goodness for epinephrine (a.k.a adrenaline) that kicks in in the clutch and makes our minds sharp when needed most.

Sometimes, when we're really dumb, we work extra hours to make a few extra bucks. For example, over Memorial Day weekend I volunteered to work at the Yuma, Colorado Hospital for a 72 hour shift. Yuma is a small town near Kansas with a 12 bed hospital. I did the same thing last year, and it was a piece of cake. I hardly worked for 2 of the 3 days, so I had high hopes for a repeat this year. I brought Elizabeth and the kids with me so that we could spend some time together.

We were all sorely disappointed, as a whirlwind of badness descended over Yuma, coinciding with my arrival for the weekend. Several major motor vehicle accidents, several major orthopedic fractures, a slovenly procession of drunks and deadbeats, a death, a premature labor, 6 patients transported emerg

ently out of town via helicopter and ambulance, and 30 ER visits later, and I was about done for. I had nothing left in the old tank. I got ZERO sleep on Friday night and the badness just kept rolling in uninterrupted until almost 24 hours later. Mercifully, I climbed zombie-like into bed around midnight on Saturday night and proceeded to get about 6 hours of uninterrupted sleep, which refilled my tank enough for me to make it through the next 36 hours. By Monday evening, the hospital nurses were only half-joking when they asked me to never come back, as they assumed it was my bad mojo that had precipitated the weekend's carnage.

When we pulled out of town late Monday night, a feeling of exhaustion, relief and triumph swept through me. I had done a very long, legendarily difficult shift. I had made a few mistakes, but had also saved a few lives, rendering quality medical care to the good people of Yuma despite some adverse circumstances. And I had accumulated a litany of war stories which I have relived with my fellow physicians over the past week.

Which may go to the question of why we sign up for the sleepless, stress-filled nights, when there are plenty of easier ways to make a buck. Why? The sense of fulfillment, the underlying compassion for humanity (sometimes masked by the necessary cynicism), the sense of purpose, the adrenaline rush, the prestige, and the glory somehow compensate for the bloodshot eyes, the mental cobwebs, and the eleven years of preceding poverty.

Is it worth it? There have been plenty of sleepless call nights when I head down to admit another drunk criminal and I feel the gaping abyss of despair open beneath me that I would have emphatically stated no. But now on the precipice of completing my training, as the attributes and skills of a physician are permanently coalescing within me, I can retrospectively state, "Yes, it has been worth it. I have climbed the mountain and can understand the purpose of what seemed to be an endless trek. Veni vidi vici."

Now, if you'll excuse me, I need some sleep

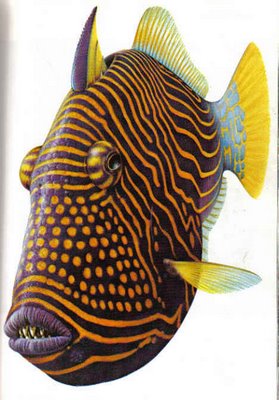

I am posting this picture now for one sole reason: I know that the instant Matt opened this page and saw this image, his heart dropped in his chest, his breath quickened, and he flushed with cold sweat-- just for an instant. Then, his rational adult brain took over and convinced him that there is nothing to be afraid of. (Right, Matt?)

I am posting this picture now for one sole reason: I know that the instant Matt opened this page and saw this image, his heart dropped in his chest, his breath quickened, and he flushed with cold sweat-- just for an instant. Then, his rational adult brain took over and convinced him that there is nothing to be afraid of. (Right, Matt?)